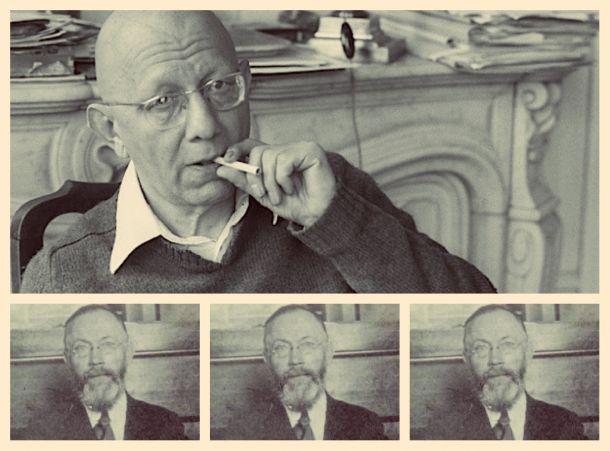

The Castoriadis-Pannekoek Exchange (1953 - 1954): Second letter

Castoriadis stresses his agreement with Pannekoek on the issue of the 'autonomy of the working class' and expresses his disagreement over the role of the revolutionary party.

Your letter has provided a great satisfaction to all the comrades of the group; satisfaction of seeing our work appreciated by a comrade honored as you are and who has devoted an entire life to the proletariat and to socialism; satisfaction of seeing confirmed our idea of a profound agreement between you and us on the fundamental points; satisfaction finally of being able to discuss with you and of enriching our review with this discussion.

Before discussing the two points to which your letter is devoted (nature of the Russian Revolution, conception and role of the party), I would like to underline the points on which we agree: autonomy of the working class as both means and end of its historical action, total power of the proletariat at the economic and political level as the sole concrete content of socialism. I would furthermore like on this point to to clear up a misunderstanding. It is not correct that we restrict “the activity of these organisms to the organization of labor in factories after the taking of social power.” We think that the activity of these soviet – or workers’ council – organisms after the taking of power extends itself to the total organization of social life, which is to say that as long as there is need for an organism of power, its role will be fulfilled by the workers’ councils. Neither is it correct that we would only think of such a role for the councils in the period following the “taking of power.” At the same time, historical experience and reflection show that the councils could not be the organisms truly expressing the class if they were created to thus decree the future of a victorious revolution, that they will be nothing unless they are created spontaneously by a profound movement of the class, therefore before the “taking of power”; and if it is thus, it is evident that they will play a primordial role during the entire revolutionary period, whose beginning is precisely marked (as I said in my text on the party in number 10) by the constitution of the autonomous organisms of the masses.

Where in contrast there is, in fact, a real difference of opinion between us, is on the question of knowing if, during this revolutionary period, these councils will be the sole organism which plays an effective role in conducting the revolution, and, to a lesser extent, what the role and task is of the revolutionary militants in the meantime. That is, the “question of the party.”

You say “in the conquest of power we have no interest in a ‘revolutionary party’ that will take the leadership of the proletarian revolution.” And even further, after having quite rightly recalled that there are, beside us, a half-dozen other parties or groups that claim to represent the working class, you add: “in order for them (the masses in their councils) to decide in the best way possible they must be enlightened by well-considered advice coming from the greatest number of people possible.” I fear that this view of things has no correspondence with both the most glaring and the most hidden traits of the current and prospective situation of the working class. Since these other parties and groups of which you speak do not simply represent different opinions on the best way to make revolution, and the sessions of the councils will not be calm gatherings of reflection where, according the opinions of these diverse counselors (the representatives of the groups and parties), the working class will decide to follow one path rather than another. From the very moment that these organisms of the working class have been constituted, the class struggle will have been transposed to the very heart of these organisms; it will be transposed there by the representatives of the majority of these “groups or parties” which claim to represent the working class but who, in the majority of cases, represent the interests and the ideology of the classes hostile to the proletariat, like the reformists and the Stalinists. Even if they don’t exist there in their current form, they will exist in another, let us be sure. In all likelihood, they will start with a predominant position. And the whole experience of the last twenty years – of the Spanish war, the occupation, and up to and including the experience of any current union meeting – we learn that the militants who have our opinion must conquer by struggle even the right to speak within these organisms.

The intensification of the class struggle during the revolutionary period will inevitably take the form of the intensification of the struggle of diverse factions within the mass organisms. In these conditions, to say that a vanguard revolutionary organization will limit itself to “enlightening with well-considered advice” is, I believe, what in English is called an “understatement.” After all, if the councils of the revolutionary period prove to be this assembly of wise men where nobody comes to disturb the calm necessary for a well-considered reflection, we will be the first to congratulate ourselves; we feel sure, in fact, that our advice would prevail if things happened this way. But it is only in this case that the “party or group” could limit itself to the tasks that you assign it. And this case is by far the most improbable. The working class which will form the councils will not be a different class from the one that exists today; it will have made an enormous step forwards, but, to use a famous expression, it will still be stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges. It will be at the surface dominated by profoundly hostile influences, to which it can initially oppose only its still-confused revolutionary will and a minority vanguard. This will be by all means compatible with our fundamental idea of the autonomy of the working class extending and deepening its influence on the councils, winning the majority to its program. It may even have to act before; what can it do if, representing 45% of the councils, it learns that some neo-Stalinist party prepares to take power for the future? Will it not have to try to seize power immediately?

I do not think that you will disagree with all that; I believe that what you aim for above all in your criticisms is the idea of the revolutionary leadership of the party. I have however tried to explain that the party cannot be the leadership of the class, neither before, nor after the revolution; not before, because the class does not follow it and it would only know how to lead at most a minority (and again, “lead” it in a totally relative sense: influence it with its ideas and its exemplary action); not after, since proletarian power cannot be the power of the party, but the power of the class in its autonomous mass organisms. The only moment when the party can approach the role of effective leadership, of the corps which can try to impose its revolutionary will with violence, may be a certain phase of the revolutionary period immediately preceding its conclusion; important practical decisions may need to be taken outside the councils if the representatives of actually counter-revolutionary organizations participate, the party may, under the pressure of circumstances, commit itself to a decisive action even if it is not, in votes, followed by the majority of the class. The fact that in acting thus, the party will not act as a bureaucratic body aiming to impose its will on the class, but as the historical expression of the class itself, depends on a series of factors, which we can discuss in the abstract today, but which will only be appreciated at this moment: what proportion of the class is in agreement with the program of the party, what is the ideological state of the rest of the class, where is the struggle against the counterrevolutionary tendencies within the councils, what are the ulterior perspectives, etc. To draw up, as of now, a series of rules of conduct for the various possible cases would doubtless be puerile; one can be sure that the only cases that will present themselves will be the unforeseen cases.

There are comrades who say: to trace this perspective is to leave the path open to a possible degeneration of the party in the bureaucratic sense. The response is: not tracing it means accepting the defeat of the revolution or the bureaucratic degeneration of the councils from the very start, and this not as a possibility, but as a certitude. Ultimately, to refuse to act in fear that one will transform into a bureaucrat, seems to me as absurd as refusing to think in fear of being wrong. Just as the only “guarantee” against error consists in the exercise of thought itself, the only “guarantee” against bureaucratization consists in permanent action in an anti-bureaucratic direction, in struggling against the bureaucracy and in practically showing that a non-bureaucratic organization of the vanguard is possible, and that it can organize non-bureaucratic relations with the class. Since the bureaucracy is not born of false ideas, but of necessities proper to worker action at a certain stage, and in action it is about showing that the proletariat can do without the bureaucracy. Ultimately, to remain above all preoccupied with the fear of bureaucratization is to forget that in current conditions an organization would only know how to acquire a noteworthy influence with the masses on the condition of expressing and realizing their anti-bureaucratic aspirations; it is to forget that a vanguard group will only be able to reach a real existence by perpetually modeling itself on these aspirations of the masses; it is to forget that there is no longer room for the appearance of a new bureaucratic organization. The permanent failure of Trotskyist attempts to purely and simply recreate a “Bolshevik” organization finds its deepest cause there.

To close these reflections, I do not think either that one could say that in the current period (and hence the revolution) the task of a vanguard group would be a “theoretical” task. I believe that this task is also and above all the task of struggle and organization. For the class struggle is permanent, through its highs and lows, and the ideological maturation of the working class makes itself through this struggle. But the proletariat and its struggles are currently dominated by bureaucratic organizations (unions and parties), which has the result of rendering struggle impossible, of deviating them from the class goal or conducting them to defeat. A vanguard organization cannot indifferently attend this show, neither can it content itself with appearing as the owl of Minerva at dusk, letting the sound of its beak fall with tracts explaining to the workers the reasons for their defeat. It must be capable of intervening in these struggles, combating the influence of bureaucratic organizations, proposing forms of action and organization to the workers; it must even at times be capable of imposing them. Fifteen resolute vanguard workers can, in certain cases, put a factory of 5,000 into strike, if they are willing to knock out some Stalinist bureaucrats, which is neither theoretical, nor even democratic, these bureaucrats having always been elected in comfortable majorities by the workers themselves.

I would like, before ending this response, to say a couple things about our second divergence, which at first glance has only a theoretical character: that of the nature of the Russian Revolution. We think that characterizing the Russian Revolution as a bourgeois revolution does violence to the facts, to ideas, and to language. That in the Russian Revolution there were several elements of a bourgeois revolution – in particular, the “realization of the bourgeois-democratic tasks” – has always been recognized, and, long before the revolution itself, Lenin and Trotsky had made it the base of their strategy and tactics. But these tasks, in the given stage of historical development and the configuration of social forces in Russia, could not be dealt with by the working class who, in the same blow, could not pose itself essentially socialist tasks.

You say: the participation of workers does not suffice. Of course; as soon as a battle becomes a mass battle the workers are there, since they are the masses. But the criterion is not that: it is to know if the workers find themselves the pure and simple infantry of the bourgeoisie or if they fight for their own goals. In a revolution in which the workers battle for “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” – whatever meaning they subjectively give to these watchwords – they are the infantry of the bourgeoisie. When they fight for “All power to the soviets,” they fight for socialism. What makes the Russian Revolution a proletarian revolution is that the proletariat intervened in it as a dominant force with its own flag, its face, its demands, its means of struggle, its own forms of organization; it is not only that it constituted mass organisms aiming to appropriate all power but that this itself went past the expropriation of the capitalists and began to realize workers’ management of the factories. All this made the Russian Revolution forever a proletarian revolution, whatever its subsequent fate – just as neither the weakness, nor the confusions, nor the final defeat of the Paris Commune prevents it from having been a proletarian revolution.

This divergence may appear at first glance to be theoretical: I think however that it has a practical important insofar as it translates par excellence a methodological difference into a contemporary problem: the problem of the bureaucracy. The fact that the degeneration of the Russian Revolution has not given way to the restoration of the bourgeoisie but to the the formation of a new exploitative layer, the bureaucracy; that the regime that carries this layer, despite its profound identity with capitalism (as the domination of dead labor over living labor), differs in many aspects that cannot be neglected without refusing to understand anything; that this same layer, since 1945, is in the process of extending its domination over the world; that it is represented in the countries of Western Europe by parties deeply rooted in the working class – all this makes us think that contenting ourselves with saying that the Russian Revolution was a bourgeois revolution is equivalent to voluntarily closing our eyes to the most important aspects of the global situation today.

I hope that this discussion can be pursued and deepened, and I believe it is not necessary to repeat to you that we welcome with joy in Socialisme ou Barbarie all that you would like to send us.

Comments

Post new comment