Workers' control in the United States of America

The United States cooperative and council movement is rooted in sustained working-class struggles against the most rapacious forms of capitalism in rural agrarian regions and, since late-19th century, expanded into urban production industries. For about 150 years, working class efforts to form cooperatives and self-organized workplaces have endured in response to predatory corporate expropriation and as a means of resisting capitalist oppression through establishing socialist self-management and workers democracy. Following the end of the US Civil War, in the 1870s, smallholding farmers struggled against wealthy robber barons who dominated commodity exchanges to oppose the crop-lien system, which offered credit that eventually forced farmers into debt peonage. Through crop-liens, merchants exploited smallholding farmers who were unable to obtain affordable credit for seeds and supplies.

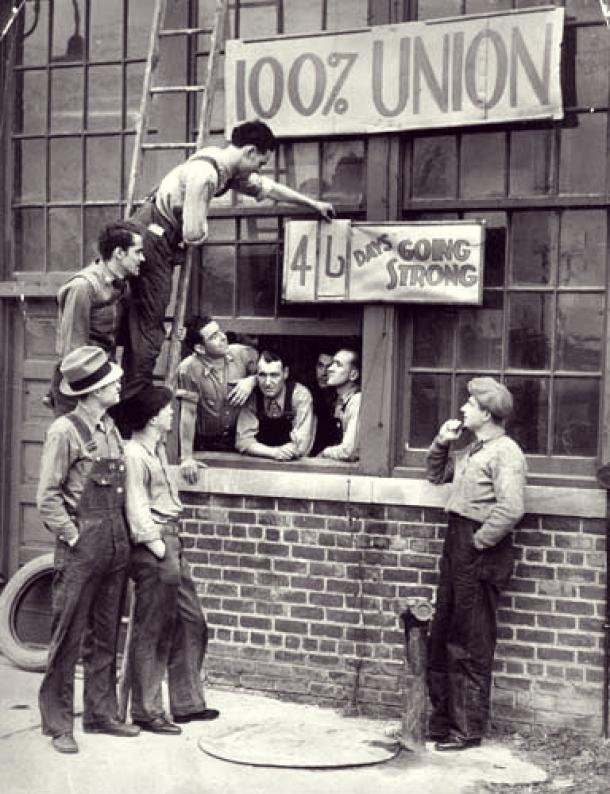

At the heart of the worker cooperative movement in the US has been a period of syndicalist organizing from the 19th century to the present in response to capitalist and state capitalist opposition and demonization. In the early 20th century, the resurgence of the cooperative or worker’s council as an alternative to corporate absolutism reflects a vision among workers that democratic unions would sweep away the mass production system and introduce an egalitarian and socialist society. Workers who gravitated toward syndicalist unions in the early-20th century also saw cooperatives as a compelling alternative to capitalism. They envisioned worker control as a means of superseding the wage system and producing for the needs of communities, rather than selling their labor to capitalists, who would appropriate the surplus and reinvest in lower-wage-labor markets and new technology.

In the first two decades of the 20th century, the capitalist class in the US consolidated power in the industrializing republic through resisting worker self-organization and formation of unions. Capitalists also opposed experimentation with practical utopias and intentional communities as a threat to their power and developed propaganda warning workers of the danger to American society while violently crushing movements for working-class power in unions. Nevertheless, in 1920, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics reported 2,600 cooperative stores and buying associations in the United States, mostly in small towns that served farm communities. But following the end of the First World War, from 1920-22, most cooperative chains, wholesalers, and federations in the United States went bankrupt and by the mid-1920s most failed and ceased operation.

By the 1960s, with the US in a state of social turmoil, worker cooperatives were an integral of the larger movement for social justice, rebelling against American individualism and materialism. Represented in the media as “counterculture,” they formed part of a counter-institutional effort in search of alternative means of organizing society. The alternative was decisively located in the vision of collective and cooperative work, in which equality was the foundation of democracy and sharing resources a means of empowerment. The social movements of the 1960s and 1970s soon dissipated, replaced by the neoliberal market-oriented Reagan administration. In the 1980s, many successful cooperatives were abandoned or bankrupted, once again leaving the actuality of worker control in the past even as demands for stable employment and democracy at the workplace remained strong.

The standing of worker cooperatives in the US is linked directly to cyclical capitalist cycles of economic recession, depression, and periods of economic recovery. In every historical era, capitalist propagandists depicted cooperatives as dangerous to society and demeaned those individuals involved in the movement for retreating into frugal and modest living. However, with the failure of classical neoliberal economic models and the Keynesian economics in the US, cooperatives and worker self organization has gained greater influence.

Notwithstanding this, throughout the last 150 years, cooperatives retained popularity. While cooperatives are vulnerable to economic cycles, just like private businesses are, during periods of relative prosperity the media and state disparaged cooperatives and promoted individualism and business ownership, despite the fact that only a small fraction of the working class could even hope to own a profitable enterprise. While American workers have always maintained a spirit of mutual aid in times of crisis, capital and the state have continually emphasized that individualism and private ownership were the only means to prosperity. During the New Deal, popular support for cooperatives waned after state intervention in the capitalist economy advanced the financial and corporate oligarchy that benefited from economic stimulus and wartime government spending.

US workers desire to form cooperatives and worker councils is rooted in their desire to control their fate and eliminate the degradation of work in the US. Since the reorganization of productive processes by corporate capitalists, American workers have been forced to work at lower wages in authoritarian businesses. As political economist David Harvey argues, in communities that are dominated by corporations engaged in “appropriation by dispossession,” asserting that modern private capitalism, with the compliance and sponsorship of the State, is resorting to pre-capitalist forms of expropriation of essential resources indispensable for human reproduction in early capitalism. The working class is not only losing their jobs, but also their homes, rights to health care, education, and to basic survival. These circumstances create the environment for the development of popular assemblies and cooperatives to establish enterprises that support communities. The growth of cooperatives and growing interest in worker self organization and worker-community councils has gained new urgency in the second decade of the 21st century.