GLOVES OFF: WHEN THE WORKERS TAKE CONTROL

A review of the book "New Forms of Worker Organization" by Immanuel Ness

In 1972-73 women machinists at the Whyalla Glove Factory were faced with redundancy as the company – James North – decided to close the factory down. The women challenged the management’s prerogative to close the factory as it saw fit, and occupied it.

The story is told by Verity Burgmann, Ray Jureidini (who seems to have done the research for the Whyalla part of the story) and Meredith Burgmann in ‘Doing without the Boss: Workers’ Control Experiments in Australia in the 1970s’.

It is one chapter in a fascinating collection edited by Immanuel Ness entitled New Forms of Worker Organization: the Syndicalist and Autonomist Restoration of Class Struggle Unionism published by PM Press out of Oakland, California.

A new form of industrial action

The basis of autonomism was the syndicalist movement and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) from 1895.

Emma Goldman defined syndicalism as organisation that “advocated at revolutionary philosophy of labor conceived… in the actual struggle and experience of the workers themselves”.

Ness in his introduction to the book outlines the approach:

• All forms of action are advanced by the workers themselves, not by union officials.

• There is total opposition to all collaboration with management.

• Independence from any political party.

• A culture of solidarity on the job and with the local community.

• Workers exhibit total solidarity and unity through wearing buttons or hats displaying their allegiance.

• The strike is a principal strategy.

• Seizing control over production is a goal.

• Opposition to any collective bargaining that cedes the capacity for direct action.

Autonomist Marxism developed a theory and ideology in Italy in the hot autumn of 1969 and spread to other European workers. Its theoretical base was developed largely by Antonio Negri (later imprisoned by Italian authorities for alleged connection to the Red Brigades, which many saw as taking direct action too far).

Italian occupations also had a pre-fascist history written about by Antonio Gramsci and others from the 1920s. For more details on this see especially Steven Manicastri’s chapter ‘Operaismo Revisited: Italy’s State-Capitalist Assault on Workers and the rise of COBAs [Comitati di Base]’.

These syndicalist and autonomist principles seem to have been put into practice, without reference to any books, by the women at the Whyalla Glove Factory.

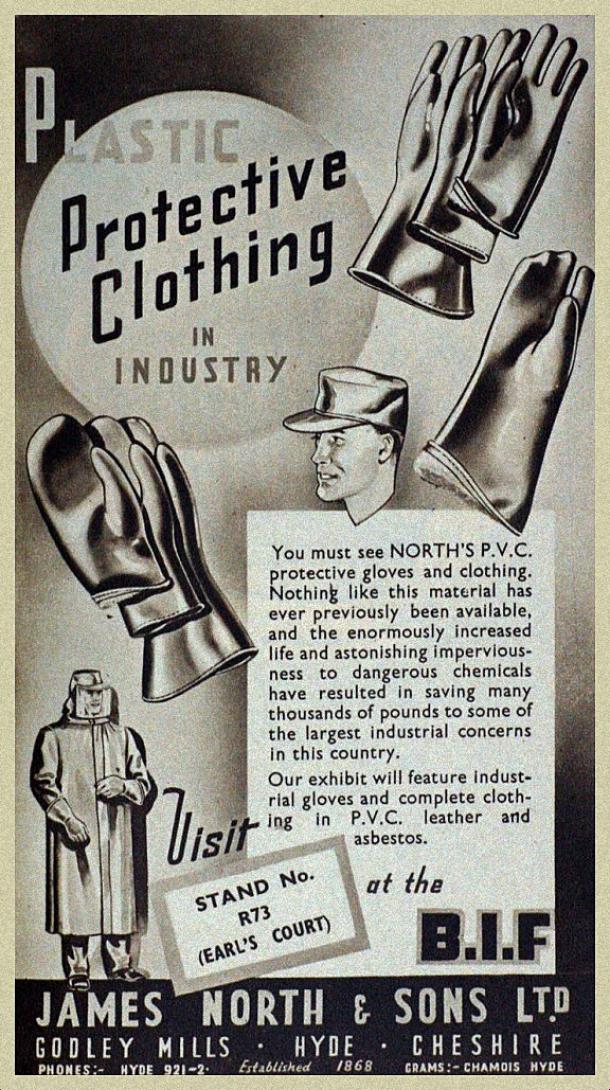

Their employer, James North and Sons, was a British company which had done well during World War Two.

“The manager was shocked and was violent towards the women who had streamed into his office,” write the Burgmanns and Jureidini.

“Barry Cavanagh was secretary of the Miscellaneous Workers Union and attested to the manager’s crazed fury. He broke the nose of at least one worker.

“The Ship Painters and Dockers’ Union members arrived not long after, acting in solidarity with the women. Cavanagh described the Dockers’ Union secretary as a little bloke but one who was “built like a drop of water upside down”. When these workers arrived the manager had no more authority.

“The gates were locked by management but the workers were quickly provided for, via windows, with mattresses, food, guitars, televisions and other useful items.”

The manager arrived the next morning to find the factory surrounded by many people supporting the workers and he asked the police to help him enter. The police informed him that they could escort him through but if anything went wrong they would not guarantee his safety. He went home.

The Ship Painters and other unionists in Whyalla, at this point, decided to form a committee and attempt to close down all industries in Whyalla (Long before BHP closed, or before a carbon tax!)

The Missos at the time were committing to strategies that were more militant, including supporting worker co-operatives.

The mainstream South Australian press predictably attacked the women and their supporters, but local news took a different approach. The local Whyalla News, generally a conservative paper, ran a strongly supportive editorial.

The sit in lasted five days, during which time the South Australian government ordered gloves, thus guaranteeing one month’s work, and giving time for the women to form the Whyalla Co-operative. It remained successful under workers’ control for nine months when it was sold to private interests who guaranteed employment.

It seems that the women’s decision to stop running the factory was prompted from outside the factory, in particular from the cultural space in Australia at the time of women being the “extra” bread earners in the home, rather than the focus of the household income. Husbands were not so keen on the extra involvement and time women spent at work away from “family duties”.

A man was appointed by the women as the manager, to utilise his knowledge of the machinery when breakdowns occurred. He was paid six times the average female wage.

He did not get full managerial prerogative however. He tried to, but was required to get collective approval for his decisions. Day-to-day decisions were included in this and all co-op members were included in consultations and decision-making.

The workers set their own pace of production, and whilst they still ensured that the factory was viable, the viability was in terms of being able to pay their own wages and ensure decent conditions, rather than extending the surplus to maximise profit − a different attitude and mode than what was required when producing for the company.

The “manager”, when the place was being run as a co-op, helped out with cutting. The same manager, when the factory was again run as a private company, adopted a totally different attitude to the women workers, becoming authoritarian and demanding obedience and “respect” when being addressed by the mere workers. He did not get it.

Work practices changed under the co-op, as they did in all the autonomous workplaces discussed in the book.

There was a commitment to collective production and decision making. Workers who were seen to be “not pulling their weight” were encouraged by the group, not reprimanded by management. Successful completion of production runs for orders was celebrated by the team.

Production was diversified from gloves to include surgical gowns, and the ingenuity of the workers given free rein in determining best ways of making things and task allocation was determined by whoever was interested, another process that changed quickly when the private firm took over.

The role of supervisor was still ascribed to one worker, Nancy Baines. Nancy explained that it was not as the name seems to imply: “You can’t supervise people who are their own bosses because you can’t give them orders.”

The role was one more of an organiser and some quality control. Conflict was almost totally removed when workers were in control. The “supervisor” ensured materials were delivered to machinists, inspected and helped out those who had troubles, rather than having a disciplinary role.

The workers had great feelings about running the factory.

“In the co-operative I took pride in the whole organisation,” one is quoted as saying.

Another worker found the co-op experience spoiled her for any other wage labour. When Spencer Gulf Clothing took over Jacqui Blakeley did not keep working there because she “did not want a bridge between my wages and the product. The company is the middleman.”

More sit-ins around Australia

The authors of the Australian chapter also consider the Sydney Opera House sit-in of 1972, the Nymboida Mine takeover (1975-79), and more lightly, the Harco steel factory (1971), Wyong Shopping Centre occupation (1974) and the Altona Union Carbide sit-in (also well observed by Barry Hill in his terrific book Sitting In).

Negri’s view was that these explosions of working class militancy and assertions of power came from the ending of the willingness of workers to accept their sublimation to the capitalist Keynesian welfare state systems and the idea that it was time to assert their power at the point of production.

A rejection by workers that their role was to use their power only within capitalist relations was occurring and the economic crises that developed from the 1970s s reasserted capitalism supremacy.

The examples outlined by the writers are reminders that “workers can do without the boss –however precariously”. They quote Joe Owens, heavily involved in the Opera House sit-in and the Wyong dispute who noted that workers’ control:

“isn’t a strategy to overcome this society and change it into a socialist society but it does give workers confidence and in it the seed of the new society that can be practised in the old.”

Comments

Post new comment