OCCUPY, RESIST AND POSE FOR THE CAMERA

Nationalisations, bailouts, economic stimulus... much has been written about these and other recent events by the corporate media in the Global North and this so-called new wave of “socialism.” Fortunately many have responded that these events are all about saving a failing neoliberal model as opposed to building any alternative.

Unfortunately there is one area where this critical response is not occurring. Comparisons are being made between the worker occupations, bossnappings and partial union ownership of corporations in the Global North with the worker co-op movements in South America, particularly the Worker Recovered Enterprise movement in Argentina (Movimiento de Empresas Recuperadas por sus Trabajadores – ERT). If one believes the hype, a sequel to the documentary The Take is about to be filmed in either North America or Europe.

It makes for a great story and these workers deserve our full support. But as with the cries of “socialism” from the right, it is an equally hollow comparison with a real movement for change.

A large part of this problem stems from a misunderstanding of the movements occurring in Latin America. It is impossible to learn from and adapt these exciting developments without examining their syndicalist and community based nature. This new wave of grassroots movements is a critical change from “centralised democracy” a previous generation imported from Leninism.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the ascendancy of the Washington Consensus had a profound effect on the entire region. Cuba’s “Special Period,” privatisations, the ascendancy of American imperialism, the collapse of the Sandinistas and others forced many in Latin America into a realisation that new models were needed to counter this powerful wave of neoliberalism. Since a global approach was an impossibility this new model had to be created in the communities were the people lived.

This is evident by three very different approaches:

- Venezuela – political change leads to economic transformation. This is the closest to the original model but it is evolving as evidenced by the focus on worker cooperatives, new roles for unions and a growing emphasis on community based initiatives.

- Bolivia – economic transformation leads to political change. The Movement for Socialism (MAS) started as a union of indigenous coca growers and their co-operatives. This economic base provided the political springboard through its “good example.”

- Argentina – economic action leads to community transformation. As workers seized their factories some of them opened them up to the communities building centres of education and activism. Some of the most promising ERTs are more interested in building new communities with each other and the community that surrounds them – what are known as economies of solidarity – instead of gaining political power in reaction to the repeated betrayals from the elites and the co-option of previous movements.

Obviously these are brief summaries but important commonalities exist across Latin America: using democracy to build an economic alternative to neoliberalism and a refreshing realisation that not one model has all the answers. Although problems exist, there is a growing confidence that as long as the movements stay grounded in the community they will withstand the challenges. Only time will tell which models (or others) will succeed but they are proving remarkably resilient and supportive of each other.

Of these models, the Argentine ERT movement is the most frequently misunderstood since there is no definitive model of how these plants are run once the workers “occupy, resist and produce.” This is a democratic process and it is the workers who determine its path. They call this “autogestion” (self-management). Overall there is a horizontal structure with elected leadership, union reps and plant direction on a “one worker – one vote” basis. It is also with some ERTs like the FaSinPat ceramic factory (formerly known as Zanon) in the province of Neuquen, a union movement. When existing unions weren’t structured to meet their needs (how do you bargain without management?); Zanon built a new union to reflect the real desire of its workers (the workers decide their priorities through union supervised votes).

With the notable exception of FaSinPat whose recovery was led by its elected union leadership, most of Argentina’s ERTs emerged from the initiatives of workers who had no economic alternative but to re-start their workplace. This isn’t a movement from above but by the workers themselves.

This distrust also extended to many union leaders due to their strategies during the Carlos Menem (President of Argentina from 1989 to 1999) years and its aftermath. Under the auspices of some of Argentina’s bureaucratic union leaders: they struck, took concessions, when privatised they took partial ownership (often with union leadership and the bosses sharing power) and campaigned for better politicians. When all else failed they seized workplaces until they received better severance or labour relations.

All strategies failed: the strikes were broken, plants still closed, the union bosses proved just as greedy as the ordinary ones, the “better” politicians were only better speakers and the excitement of the occupations quickly dissipated once the severance cheques were spent or until the next management salvo.

The reason for these failures is clear: no consideration was given to any other model but a kinder form of neoliberalism with better bosses and governments. This proved fatal and many of the working class turned against them. Even worse, with so many factories closed and workers forced into precarious jobs, the traditional model of industrial unionism no longer even applied in many sectors of the economy.

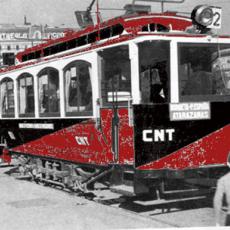

The unions that worked with these activists built new bases of solidarity (e.g. Buenos Aires transit workers). Unfortunately many others openly sided with the elites and worked against this movement as their leaders perceived it as a threat to their own vertical structures.

EL NORTE

Given this historical context, it’s clear that the recent northern wave of plant occupations, bossnappings, worker ownership schemes and comparisons to the Argentine ERT movement are completely unfounded. It is the period before this movement that is applicable as these responses, though valiant, have an ultimate purpose of fixing a failing model.

The Washington Consensus has moved north and we are now entering its logical outcome of de-industrialisation. With 40% of Torontonians now employed in precarious work, traditional union and political responses are meaningless in a community that is breaking apart.

This is a global agenda and we must examine other successful models of resistance and empowerment to counter it. These need to be adapted to Canadian realities with an understanding of previously successful responses to these inherent failings of capitalism.

Of the three models mentioned, the Venezuelan approach has been the most tried and the biggest failure. Years of effort have been put into building a mass political movement, discussing new political parties or reforming existing ones. All this effort has not led to Hugo Chavez but to former Ontario Premier Bob Rae. The realities of our electoral system, the rightward drift of the Canadian working class, the corporate media and the entrenched power of the elites ensures this approach will continue to fail unless new bases of support are built.

The model that has led to political gains has been the Bolivian approach.

In Saskatchewan the CCF used the “good example” of the cooperatives to obtain political power which allowed their “good example” of public health care to be nationally copied.

In Winnipeg its impossible to talk about the city’s rich communist past without acknowledging the role the People’s Co-Op played in its success. Unlike other consumer co-ops, it was established with a distinctly political purpose (its first Collective Agreement began with a statement that management and workers were united in overthrowing the capitalist system). It was an economic anchor in the community that provided employment to its activists. This “good example” countered the relentless red scare campaigns it endured.

Both the co-op and Winnipeg’s elected communist politicians continued into the 1980s, something unheard of anywhere else in North America. When these traditions ended; pressure from the left ended.

These are not perfect examples but one can’t deny the beneficial effects they have had. This is a problem that must be addressed: as long as many in the left are debating or trying to build the perfect example; we will continue to fall behind. Neoliberalism will not wait for us to get our act together.

Finally we must discuss the Argentinean example. Aside from the causes of this movement and our experiences with de-industrialisation, there appears to be little else in common.

The employee / union ownership model being established in North America merely re-inforces corporatism with workers paying the bills and no discussion about controlling production for their purposes. This rejection of control and any horizontal (democratic) structure allows the bosses to continue their agenda.

An example of this can be seen at United Airlines where workers purchased their company. The only thing that changed was management was now able to blackmail the workers “to save their investment” by cutting costs through more concessions. The height of this folly occurred when the workers agreed to end their defined benefit pension with only one exception: the CEO was allowed to keep his.

Imagine if instead of turning on each other, the workers would have used their ownership to establish a horizontal structure saving millions by wiping out layers of unnecessary management?

There exists a misunderstanding of the worker co-op concept amongst many activists and even within some Canadian worker co-ops themselves. No matter how they self-identify, many workers’ co-ops in Canada do not embrace the concept of horizontalism much less building an alternative to capitalism. Being anti-corporate means nothing if managers are renamed “members” who still control non-voting employees and merely use the more efficient co-operative structure for increased profitability.

Clearly, it’s easy to see how the Argentine experience is not applicable. However when one looks at the roots of the progressive Canadian movement a different picture emerges.

In the late 19th century when no viable political alternatives existed and the union movement was predominantly craft based, excluding most of the working class, the U.S. based Knights of Labor arrived. Their democratic structure and community based approach (any community with 10 members could form a Local Assembly) resulted in over 300 assemblies and 20,000 members within a decade. As a result of their commitment to invest 50% of all dues into local economic initiatives, worker cooperatives were established either by buying out existing industries or establishing new ones to meet local needs. For the first time many workers felt empowered and although many of these endeavours failed, it was this empowerment that stayed with them. Inevitably it was some of their odious practises (including racism against Chinese workers) and their limited goals that proved their undoing. But for the first time a new approach was tried and this activism created a mood for change unleashing even better movements.

It is this spirit of community-based empowerment that is at the heart of the ERT movement.

Canada today shares growing parallels with the conditions that led to the arrival of the Knights. Today’s elites are enjoying levels of power not seen since the days of the Robber Barons and the Family Compact. There is growing resentment to the current union movement with many workers resentful of their better wages / benefits (as existed toward the craft unions). Many are excluded from joining a union due to a structure that was never designed to accommodate them. To give an example, how can a union organise workers who are paid per call for pizza orders from their home?

COMMUNITY BASED UNIONS

As the industrial model continues to break down new bases of support will be required. Without a legal means for unemployed activists to remain in the union they will drift away from the movement. Unions need to examine the concept of community based locals and membership. These Community Locals can provide several services: education programmes, workplace assistance (such as Employment Standards), Human Rights, etc. This will create key democratic centres within the community just as the Red Halls and Labour Temples did in the past.

For this to be successful, our unions need democratic renewal to end its centralised democratic tendencies. This can only be done by adopting a horizontal structure to reflect its membership instead of a vertical one that reflects the corporations it bargains with.

New union models will also be needed. This shouldn’t be viewed as a negative as our movement was never stronger than when workers could fight for their rights through three distinct models: industrial (TLC / CLC), communist (WUL) and syndicalist (IWW / OBU). Most of all, unions need to end their support of neoliberalism.

These examples typify everything wrong with the movement’s current direction:

The Ontario Teacher’s Pension Plan (OTPP) has ownership stakes in several corporations to improve its rate of return. One of those assets is the anti-union voice of the establishment – CTVglobemedia. Instead of transforming it into a voice for the people, its appointed management took a hard line at the bargaining table causing all future workers to not be eligible for the Globe’s defined benefit pension plan.[1]

At the same time the OTPP – which owns 100% of property developer Cadillac Fairview – tabled a “final offer” to its unionised workers that “proposed to eliminate employees, force workers to reapply for their jobs, restrict union representation and undermine bargaining rights.” When the workers rejected these ridiculous demands they were locked out, replaced by contract workers and then terminated.[2]

The Teacher unions have followed the current union model perfectly by bargaining a great pension for their members. In the end this model has caused one group of workers to lose their pension plan and another to lose their jobs to pay for it.

We can’t complain about the abuses of capitalism unless we recognise the role we are playing in its success. We need to take away this source of capital from the exploiters and invest it in rebuilding our communities. This can begin right now with the many corporations already owned by workers and their pension plans.

We need to revisit the concept of democratising our workplace. This is far more than merely unionising it; this is transforming it into a union of workers under their democratic control and direction. With new sources of investment from worker’s pension plans, workers can make this possible. A good place to start would be workplaces that were profitable but closed due to production moving to lower wage jurisdictions provoking a community backlash (e.g. the Hershey chocolate plant in Smiths Falls).

In Canada, we are quickly reaching the point that if we continue using strategies that haven’t changed in sixty years we will see an accelerating collapse of our communities and a worsening political reality. This is our challenge and the discussion we need to have.

Part of this discussion should ask questions we stopped asking far too long ago: Why is it always the workers who have to justify their jobs? Why do workers even need management? Any worker will tell you the operation always runs better when they’re not around. Imagine what kind of union movement could be built if management wasn’t in the way?

This discussion needs to encompass many movements and allow them to develop their own models under a united framework for change. This Confederation of Movements will allow a flourishing of democracy, community renewal and build a new solidarity economy.

Action also needs to be taken to make this happen. Here are just some ideas:

- Thousands of workers are receiving severance cheques that could be spent on building a new economy instead of establishing themselves as a “self-employed entrepreneur” (the fastest growing job title in Canada).

- Union “Job Support Centres,” established when plants close, can be transformed into “Job Recovery Centres” that assist workers in recuperating or establishing new plants.

- Community activists can join the same Credit Union, win elections and transform them.

- Unions can build new links with worker co-ops that are trying to make a difference such as Neechi Foods in Winnipeg and Planet Bean in Guelph.

Obviously there is much more that needs to be done. This article is merely in response to the comparisons of periodic moments of worker frustration and union activism with the far more meaningful worker movements occurring in South America. Yes these incidents of direct action are a good start but unfortunately they won’t lead anywhere unless we build an economic base for change.

There are movements happening in North America that are fighting for change. One example is the Take Back the Land movement in Miami where community activists are reclaiming foreclosed homes and turning them over to the homeless. They are saving communities and adding value to them by restoring these decaying homes. People are rising in support of these actions causing the police and politicians to not take action.[3] It is these types of movements that should be compared with the ERTs’ attempts to rebuild their communities.

As fate would have it, I just received a letter from the Federal NDP asking me to “join Obama’s inner circle” (they are now using Obama’s strategists) and help the NDP “build our breakthrough.” As cringe worthy as this letter is, many Canadians see the NDP as the voice of the political left. I couldn’t think of better reason why new ideas, movements and political parties are urgently needed in this country to change this perception.

Clearly we have a lot of work to do.

- cnews.canoe.ca/CNEWS/MediaNews/2009/07/06/10042411-cp.html

- www.newswire.ca/en/releases/archive/ July2009/17/c6918.html

- www.nytimes.com/2009/04/10/us/10squatter.html

Comments

Post new comment